By Ashley Lister

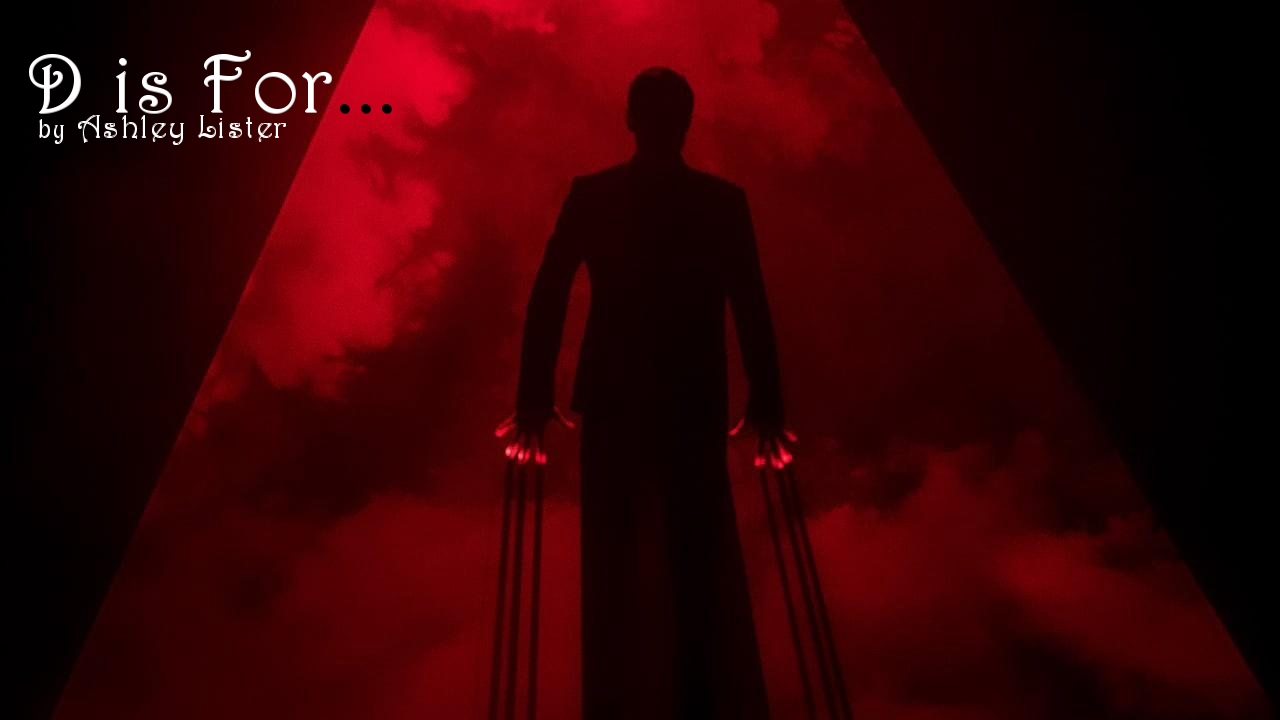

It will come as a surprise to no one that Count Dracula, Bram Stoker’s fictional creation, has been portrayed in more than 200 films. This number, second only to Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s creation, Sherlock Holmes, illustrates the power that Dracula still has over contemporary audiences.

Writing theorists (and I’m one of them) will argue that there are a very small number of plots. It’s perhaps illustrative of this point that we see stories of Dracula being told again and again and again for the entertainment of critically undemanding audiences. Without wishing to sound reductive, a typical Dracula story begins with someone feeling a little anaemic; an informed hero makes the connection between the puncture wounds on the anaemic’s neck and the newcomer to town (who is never seen during daylight hours). Then there’s a scene with a stake, some pointy teeth, and a crucifix, just before the end credits roll.

Again, I have to insist, I’m not criticising Dracula’s stories. I’m just pointing out that they typically follow a familiar structure. And this is the point I want to discuss today: why do they remain so perennially popular?

Bram Stoker’s novel was published in 1897, toward the end of Victoria’s reign. Most of us acknowledge that the Victorian period was a time of sexual repression, and that seems to be reflected in the content of Dracula. The villain is a predator who, in the late of night, inveigles his way into the private bedchambers of vulnerable young women. This same villain instigates a very intimate kiss that involves an exchange of bodily fluids and leaves his victim drained with all their energy spent.

Nowadays this motif would probably be ridiculed for being too obvious an illustration of the dangers of having illicit sexual congress. However, back in Stoker’s day, this notion entertained readers enormously and most readers didn’t make the connection between violation of social norms and the taboo behaviour of vampires.

Of course the vampire story was not Stoker’s original creation. In the 1840s, James Rymer and Thomas Prest published their Varney the Vampire stories as a series of penny dreadfuls. Even further back, in 1816, at Villa Diodati in Geneva, whilst Mary Shelley was writing Frankenstein, and Percy Shelley was having drug-fuelled nightmares about a woman who had eyes where her nipples should be, one of Byron’s other house guests, John Polidori, was penning a story later published under the title The Vampyre.

All of which is my way of saying that the fear of sex and sexuality is not specifically a Victorian attribute. Sex is a taboo topic. It leaves us exposed and vulnerable. Consequently, it’s no surprise that readers have anxieties with regards to what might happen in a sexual encounter and these fears are well-illustrated in vampire fiction.

Just as the original Dracula represents the predatory black and white dangers of Victorian melodrama, we can see how different ages give us different vampires to reflect our collective fears. Christopher Lee’s Hammer Dracula (Lee played Dracula in the films from Hammer studios. He didn’t play Dracula wielding a hammer) in the 60s and 70s showed these creatures of the night preying on the same naïve young adults who were being hurt by their involvement in the flower power movement and the sixties drug culture. Anne Rice’s vampires, brooding, self-obsessed and proudly omnisexual, first appeared at the same time as AIDS was being reported in the global media. Joss Whedon’s vampires turned from desirable individuals, who could easily pass for normal, to twisted monsters intent on slaking a specific thirst: a succinct metaphor for the bipartisan politics of the noughties that still has echoes in today’s culture.

All of which suggests that, no matter how many times we thrust that phallic stake through the vampire’s heart, it’s a creature that’s going to remain with us for many years to come. Future vampires won’t necessarily be feeding off our blood, but they’ll certainly be feeding off our anxieties, whatever those anxieties turn out to be.